Historical Periods of Jewish Mysticism

by Prof. Elliot R. Wolfson

by Prof. Elliot R. WolfsonBiblical Precursors

The Hebrew Bible is a primary source of reflection and inspiration

for virtually all branches of Jewish Mysticism and Esotericism. While we

must be careful not to conflate the religion of the ancient Israelites

with later periods of Jewish history, it remains clear that certain

elements of continuity remain throughout. One of the most important

ideas of biblical religion to impact Jewish mysticism is the phenomenon

of prophecy and revelatory experience. The texts relating the

revelations to Abraham, Isaac, Jacob, Moses, the people of Israel as a

whole at Sinai, and the prophetic inspirations and visions of Ezekiel,

Daniel and other prominent personalities in the Bible serve as the

foundation for much of the esoteric and mystical traditions of Judaism.

The Zohar, for example, is organized as a commentary on the Torah, and

contains many descriptions of experience of the Divine that approximate

descriptions of prophetic revelation found throughout the Bible.

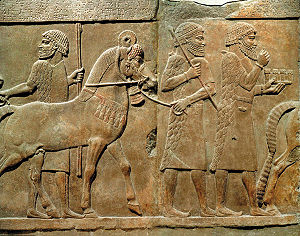

1st – 7th centuries- Early Jewish Mysticism and Esotericism

The earliest stages of post-biblical Jewish Mysticism and Esotericism

begin in the ancient Near East with a number of important texts that

draw upon biblical images, such as Ezekiel’s vision of the divine

chariot or merkavah, and the ascension of Enoch. The Rabbinic literature

of the Talmud and Midrash also contains many images and ideas about the

mysteries of the divine realm, the nature of prophecy, the origins of

the cosmos, the nature of the human soul, and other matters that went on

to have a significant influence on Jewish mysticism.

Important Texts

Sefer Yesirah (2nd – 7th centuries CE)

Sefer Yesirah

or “The Book of Creation” is a short treatise of less than 2,000 words

that discusses the creation of the universe by means of the 22 letters

of the Hebrew alphabet and the “ten ineffable sefirot.” It is unclear

what the ten sefirot exactly are in this context, but it would seem that

they refer to entities in the divine realm that are incomprehensible by

the human mind, yet nonetheless represent the mysterious nature of God

and serve as his tools in the creative process. The focus on the

symbolism of the ten sefirot and the letters of the Hebrew alphabet in

Sefer Yesirah had a major impact on later Jewish Mysticism and Kabbalah.

The symbolism of the ten sefirot is re-emphasized in an innovative and

powerful way in the kabbalistic texts that begin to emerge in Southern

France in the late 12th century.

Rabbinic Literature

Esoteric speculation can be found in many places in Rabbinic

literature. In one famous example in Mishnah Hagigah 2-1 we read,

“forbidden sexual relations may not be expounded before three [or more]

people, nor the account of creation [ma’aseh bereishit] before two [or

more], nor the account of the Chariot [ma’aseh merkavah] before one,

unless he is a sage who understand through his own knowledge.” These

categories of forbidden or restricted speculation indicate a tradition,

already active in the first few centuries of the Common Era among the

rabbinic elite, of secret knowledge regarding God, the creation of the

universe, and human sexuality. In one cryptic passage in the Talmud,

Sanhedrine 65b, we read, “Rav Haninia and Rav Oshaya used to sit the

entire day before the commencement of the Sabbath and study the Sefer

Yesirah. They created a calf one third the normal size and ate it.”

While it remains unclear whether the Sefer Yesirah referred to in this

Talmudic text is connected to the Sefer Yesirah mentioned above, it is

yet another example of esoteric traditions among the scholars of the

Rabbinic period.

Heikhalot/Merkavah Literature

Another group of Jewish mystical texts from the first centuries of

the Common Era is the Heikhalot “Chamber” and Merkavah “Chariot”

literature. These texts discuss the means of traversing the seven

chambers that surround the divine throne or chariot. Each stage of the

journey involves entering through the gateways between the courtyards,

which are guarded by angels. Only those who are fully adept in the

proper recitation of the angelic names can enter and exit unharmed.

These visions of the courtyards and throne room of God are reported in

the name of famous personalities from the Rabbinic schools, such as

Rabbi Akiva and Rabbi Ishmael. The precise connections between this body

of literature and the Rabbinc authors is difficult to determine, but

most scholars agree that the traditions related in the Heikhalot and

Merkavah literature, especially those texts from the Heikhalot Rabbati

and Heikhalot Zutarti collections, date to the Rabbinic period.

Shiur Komah

One of the most arcane texts from the ancient period of Jewish

mysticism and esotericism is the unusual collection of passages referred

to as the Shiur Komah, or “Measure of the Stature.” These texts

describe the Glory of God in the form of a supernal human body of

enormous proportions with names associated with each of the limbs. In

later periods of Jewish Mysticism anthropomorphic representations of God

plays an important role.

7th – 11th centuries- Mysticism in the Geonic period

Much of what we find from the 7th – 11th centuries reflects a strong

influence from the rabbinic and Heikhalot/Merkavah sources. A number of

important ideas that developed during this period that had a key impact

on later Jewish mysticism. The first major idea that took shape during

this period is the re-conceptualization of the Shekhinah “Divine

Presence” as more than a name for the presence of God in the world, but

rather a kind of hypostasis or entity that can interact with God.

Furthermore, it is during the Geonic period that the Shekhinah is

associated with the kenesset yisrael, “the community of Israel,” the

idea of gilgul or reincarnation finds its first appearance in Judaism,

and the technique of employing gematria “numerology” to the values of

Hebrew letters and words in order to uncover sodot or “secrets” hidden

within biblical texts becomes widespread.

Two important commentaries on Sefer Yesirah were composed during this

period, one by Shabbtai ben Abraham Donnolo (913 – ca. 982), and

another by Judah ben Barsillai al Barceloni (late 11th – early 12th).

Other important figures from this period included Eleazar Kallir (ca.

6th-8th century), Saadiah ben Joseph Gaon (882-942), Hai Gaon (939 –

1038), Hananel ben Hushiel (d. 1055-56), Nathan ben Yehiel of Rome (d.

1110), Ahima’az of Oria (11th century), and Aaron of Bagdad (mid 9th

century).

During the early part of the Geonic period most of the important

authors were centered in Babylonia, but toward the end of the period,

many of these ideas begin to spread to the Jewish communities of Europe.

12th – 13th centuries- Medieval Jewish Mysticism and the Rise of Kabbalah

Hasidei Ashkenaz

A significant development in the promulgation of mystical and

esoteric ideas in the Jewish Communities of Western Christendom was the

emergence of a group in the Rhineland known as the Hasidei Ashkenaz or

German Pietists. This movement was active from roughly 1250-1350 and had

a profound impact on the kabbalistic circles in Spain in the latter

part of the 13th century. The three main figures of this group come from

the Kalonymide family, starting with Samuel the Hasid (mid 12th

century), son of Rabbi Kalonymus of Speyer; Judah the Hasid of Worms (d.

1217), and Eleazar ben Yehudah of Worms, who died between 1223 and

1232. While little of the literary activity of Samuel the Hasid remains,

many associate the Sefer Hasidim “Book of the Pious” with the teachings

of Judah the Hasid. Eleazar of worms composed numerous works – some of

considerable length – that have survived and serve as the most important

evidence of the mystical, theological and theosophical speculations of

this group.

The Hasidei Ashkenaz placed particular emphasis on ascetic

renunciation and ethical discipline. Fasts, abstinence, physical pain

and discomfort, and even valorization of martyrdom were all regarded as

vehicles to enable mystical illumination, especially in the form of the

visualization of the Shekhinah or Divine Presence. God, according to the

Hasidei Ashkenaz, is unknowable in his essence, yet he fills all

reality and suffuses all being. By practicing ascetic renunciation and

contemplating the traditional teachings of the divine mysteries

regarding creation, revelation, and the meaning of the Torah, members of

this school believed that they could attain the pure love of God in an

encounter that was often described in ways that indicate a strong

influence from the Heikhalot and Merkavah literature, as well as the

Sefer Yesirah. Many scholars believe that the tribulations of the

Crusades and the ascetic practices of the surrounding Christian monastic

communities had an impact on the particular form of religious and

mystical piety of the Hasidei Ashkenaz.

Kabbalah in Provence and the Sefer ha-Bahir

In the 1180’s a text emerged in Provence region of southern France

that has come to serve as a defining moment in the history of Jewish

mysticism and esotericism. This text, known as the Sefer ha-Bahir or

“The Book of Brightness,” is written in the style of an ancient rabbinic

midrash. The book has a complex origin and contains at least some

elements that are believed to reflect ancient Near Eastern Jewish

traditions. Determining exactly what proportion of the Bahir derives

from ancient tradition and what was the innovation of authors living in

12th century Europe remains a question in the scholarship. The most

significant feature of the Sefer ha-Bahir is its focus on the ten

sefirot as the ten luminous emanations of God that symbolically reveal

the realm of inner divine life. The sefirot thus become living and

dynamic symbols that represent the unknowable and ineffable secrets of

God. By embracing the paradox of a symbolic system of ten divine

emanations that represent that which is impossible to represent, the

Bahir takes a decisive step that permanently changes the history of

Jewish mysticism. Kabbalah refers to those texts that employ the

theosophic symbolism of the ten sefirot, while Jewish Mysticism and

Esotericism is a broader term includes the earlier texts that do not

discuss the sefirot in exactly this manner.

Around this time we also find traditions that associate esoteric

speculation with a number of important rabbis in southern France.

Abraham ben Isaac of Narbonne (1110-1179), Abraham ben David of

Posquiers (1125-1198), also know as Rabad, and Jacob Nazir of Lunel (d.

late 12th century) are known to have endorsed kabbalistic and mystical

teachings, though little more than a few scattered hints to that affect

have been preserved in their own writings. Isaac the Blind (d. ca.

1235), son of Abraham ben David, lived in Narbonne and was the first

major rabbi in Europe to specialize in Kabbalah. Most of Isaac the

Blind’s teaching were disseminated orally to his students, and only one

text, a commentary on Sefer Yesirah, is regarded as his own composition.

This commentary is a notoriously difficult text that discusses the

sefirot mentioned in Sefer Yesirah in a theosophical manner. One

important contribution found in Isaac the Blind’s commentary is the

development of the idea that the sefirot emanate from an absolutely

unknowable and recondite aspect of God known as ein sof, or “without

end.”

Kabbalah in Gerona

In the beginning of the 13th century Kabbalah spread to Spain when

the students of Isaac the Blind began moved to Gerona, in the region of

Catalonia. Here for the first time books were composed on Kabbalah that

were designed to bring these ideas to a wider audience. Some of the most

important individuals from this period are Judah ibn Yakar (Nahmanides’

teacher), Ezra ben Shlomo (d. 1238 or 1245), Azriel of Gerona (early

13th century), Moses ben Nahman, also known as Nahmanides (1194-1270),

Abraham ben Isaac Gerundi (mid 13th century), Asher ben David (first

half of the 13th century), and Jacob ben Sheshet (mid 13th century). In

an intriguing letter sent to his students in Gerona, Isaac the blind

urges them to stop composing books on Kabbalah, for fear that these

ideas could be spread to individuals who would not take them seriously,

making them “the subject of jokes in the marketplace.” Despite Isaac the

Blind’s criticisms of the literary activities of the Gerona kabbalists,

treatises on Kabbalah continued to circulate, and soon spread to other

communities in Spain. The influence of Nahmanides at this time was

undoubtedly essential for the legitimization of Kabbalah in the Spanish

Jewish communities of Catalonia, Aragon and Castile.

Kabbalah in Castile

In the middle of the 13th century Kabbalah spread to Jewish

communities living in the cities and towns of Castile. Jacob ben Jacob

ha-kohen (mid 13th century) and Isaac ben Jacob ha-Kohen (Mid 13th

century) became known for their Gnostic teaching of a demonic realm

within God from which evil in the world originates, composed of a set of

“sefirot of impurity” that parallel the pure sefirot of God. Their

pupil, Moses of Burgos (c.1230/1225 – c. 1300), as well as Todros ben

Joseph Abulafia (1220-1298), were significant rabbinic and political

leaders of the Castilian Jewish community who wrote important works of

Kabbalah. Moses of Burgos was the teacher of Isaac ibn Sahula (b. 1244),

author of the famous poetic fable Meshal ha-Kadmoni (1281), as well as a

kabbalistic commentary on the Song of Songs. Also active in Castile at

this time was Jacob ha-Kohen (mid 13th century), who wrote a kind of

Kabbalah that he claimed to be based upon his own visions, and Isaac ibn

Latif (ca. 1210-1280), whose writings strike a very delicate balance

between kabbalistic symbolism and philosophical speculation.

From the 1270’s through the 1290’s a number of important and lengthy

kabbalistic books were written by Joseph Gikatilla (1248-1325) and Moses

de Leon (1240-1305). These two figures were among the most prolific of

the medieval kabbalists, and many of their compositions, such as

Gikatilla’s Sha’are Orah “Gates of Light,” went on to become seminal

works in the history of Kabbalah. This period of remarkable kabbalistic

literary productivity took place during the controversy over the study

of Aristotelian philosophy, especially as it took shape in the

philosophical works of Moses Maimonides, and the pronounced increase in

Christian anti-Jewish proselytizing in western Europe. Both of these may

have been a factor in the development of Kabbalah during this decisive

moment in its history.

Abraham Abulafia

Abraham Abulafia was born in Spain in 1240 and died some time after

1292. He propounded a kind of Kabbalah that, in addition to many of the

typical theosophical motifs, focused on meditative techniques and

recitation of divine names, letter permutation, numerical symbolism of

Hebrew letters known as gematria, and acrostics, designed to bring one

to a state of ecstatic union with God and to attain prophetic

illumination. The goal of this mystical and prophetic experience is to

untie the “knots” binding the soul to the body and the world. According

to his own testimony, Abulafia wrote 26 books of prophecy based on his

mystical experiences. Abulafia traveled widely and may have had

messianic pretensions. He attempted to have an audience with Pope

Nicholas III in 1280 possibly in order to declare himself the messiah.

In the 1280’s Solomon ben Abraham ibn Adret of Barcelona (c. 1235-1310)

led an attack against him and had Abulafia and his works banned because

of his claims that his writings were on a par with those of the biblical

prophets. Abulafia was a prolific writer who in addition to his

prophetic works – of which only one, sefer ha-Ot, has survived – wrote

many books on topics such as Maimonides’ Guide for the Perplexed,

commentaries on Sefer Yesirah, and descriptions of meditative

techniques.

The Zohar

During the 1290’s in Castile a kabbalistic commentary on the Torah

began to circulate that would go on to have a monumental and

transformative impact on Judaism and the West. This commentary was

written in Aramaic in the name of important Rabbis from the time of the

Mishnah in the second century CE. The most prominent Rabbi mentioned in

this collection of Kabbalistic writings is Rabbi Shimon bar Yohai. By

the end of the 13th century, these texts came to be known by a number of

names, but the one that stood the test of time was Sefer ha-Zohar, or

“The Book of Splendor.”

A careful reading of the text of the Zohar – which, in its printed

form, is almost two thousand pages in length – reveals a pronounced

influence of Heikhalot and Merkavah imagery, the writings of the Hasidei

Ashkenz, the kabbalists of Provence, Gerona and Castile, as well as

some important medieval Jewish thinkers and philosophers such as Judah

Ha-Levi and Moses Maimonides. Moreover, a number of foreign words of

Spanish origin are found in the text. This has lead scholars to the

conclusion that most if not all of the Zohar was composed in Castile

toward the end of the 13th century. The earliest citation of a passage

from the Zohar literature is found in Isaac ibn Sahula’s Meshal

ha-Kadmoni from a part of the Zohar called the Midrash ha-Ne’elam. It is

only in the later 1290’s and early 1300’s that we find Jewish scholars

citing the Zohar with any consistency.

Gershom Scholem argued that the Zohar was written in its entirety by

Moses de Leon. This position has been revised by Yehuda Liebes, who has

argued that the Zohar is in fact the product of a group of Spanish

kabbalists from the late 13th century in which Moses de Leon is a

prominent or perhaps even leading member, but which also includes Yoseph

Gikatilla, Todros Abulafia, Isaac ibn Abu Sahula, Yoseph ha-ba

mi-Shushan ha-Birah, David ben Yehudah he-Hasid, Yospeh Angelet, Yoseph

Shalom Ashkenazi, and Bahya ben Asher.

The Zohar represents in many ways the culmination of a century of

tremendous kabbalistic creativity and productivity that began in

Provence in the late 12th century and ended in Castile in the late 13th

century. The long and rambling poetic discourse of the Zohar engages

with everything from the emergence of the ten sefirot from the inner

reaches of God and ein sof, the mysteries of creation, the process of

revelation, the mystical meaning of the mitzvoth or commandments of

Jewish law, meditations on the gendered and highly erotic interactions

of the sefirot, expressed in particular in the desire for the Shekhinah,

the tenth and lowest of the ten sefirot, to return to her male

counterpart and be re-assimilated into God. The authorship of the Zohar

argues, in keeping with trends in Kabbalah from earlier in the 13th

century, that it is by means of the actions of Jews in the physical

world – especially though the performance of commandment and the study

of Torah – that the sefirot can be unified and the upper and lower

realms can be perfected. These ideas are delivered in a highly cryptic

style that presumes that the reader is familiar with many of the main

principles of Kabbalah, as well as the biblical and rabbinic

literatures. The Zohar encodes its kabbalistic message in a highly

complex set of symbols that are in turn said to be only the uncovering

of mysteries that are all contained within the words and even the

letters of the Torah.

14th – 16th centuries- From the Spanish Expulsion to the Safed Community

By the 14th century Kabbalah began to spread throughout Western

Europe, North Africa and the Middle East. Treatises such as Ma’arekhet

ha-Elohut written by an anonymous author in the early 14th century,

along with the commentary on the Torah by Bahya ben Asher and the

sermons or Drashot of Joshua ibn Shu’aib (first half of the 14th

century), served to spread Kabbalah to wider audiences. Shem Tov ben

Abraham ibn Gaon of Soria (13th – 14th centuries) and Elhanan ben

Abraham ibn Eskira (13th – 14th centuries) became important kabbalists

in Palestine, along with Isaac ben Samuel of Acre (late 13th – mid 14th

century), whose Me’irat Einaim became a seminal exposition of the

kabbalistic meaning behind the hints and allusions to secret teachings

in the works of Nahmanides. Kabbalah began to spread to Italy in the

early 14th century through the works of Menahem Recanati, who wrote a

popular Kabbalistic commentary on the Torah and a book on the mystical

meaning of the commandments. Menahen Ziyyoni of Cologne and Avigdor Kara

became important kabbalistic authorities in Germany, while Isaiah ben

Joseph of Tabriz spread Kabbalah to Persia and Nathan ben Moses Kilkis

wrote his Even Sappir in Constantinople. Two important works written

some time in the second half of the 14th century, Sefer ha-Peli’ah, a

commentary on the first section of the Torah, and Sefer ha-Kanah,

concerning the kabbalistic meaning of the commandments, argue that

Jewish law and tradition can only be properly understood according to

the Kabbalah, and that both the philosophical and literalist

interpretations of Judaism are misguided. A similar sentiment is

expressed in the writings of Shem Tov ibn Shem Tov, who attacked the

philosophical teachings of Maimonides and blamed them for the growing

trend of Jewish conversion to Christianity in Spain in the late 14th

century.

Kabbalistic literary activity began to decline in Spain during the

15th century leading up to the expulsion of the Jews in 1492. Though

there were important kabbalists still living in Spain during the mid to

late 15th century, such as Joseph Alcastiel, Judah Hayat, Joshua ben

Samuel ibn Nehmias, Shalom ben Saadiah ibn Saytun and others, many began

to migrate even before the expulsion.

The exile of the Spanish Jewish community facilitated the spread of

Kabbalah to many centers around the Mediterranean. In Italy there were

active schools of kabbalists in the late 15th century including Reuben

Zarfati, Jonathan Alemano and Judah Messer Leon, who undoubtedly had an

impact on the development of Christian Kabbalah by Giovanni Picco della

Mirandola. In North Africa during the late 15th and early to mid 16th

centuries, Abraham Sabba, Joseph Alashkar, Mordecai Buzaglo and Shimon

ibn Lavi were active teachers and writers.

By the late 1530’s, Safed had become the most important center in the

world for kabbalists. Joseph Karo, a Spanish exile who grew up in the

vibrant Jewish communities of Adrinopol and Salonika in Greece and

became one of the most prominent rabbinic figures of all time, moved to

Safed in 1536. There he composed his legal code, the Shulkhan Arukh, and

served as the head of the Beit Din, or Jewish court. Karo was also a

accomplished kabbalist who recorded a series of visions and revelation

that he received from a maggid or angelic voice in a work entitled

Maggid Meisharim. Solomon ben Moses Alkebetz, the author of the famous

Jewish liturgical poem Lekha Dodi, sung on Friday nights during the

Kabbalat Shabbat service, along with his son-in-law and pupil Moses ben

Jacob Cordevero, also moved from Greece to Safed around this time.

Cordevero, who studied with Karo, went on to have an enormously

productive career as both a teacher and a writer. He composed extensive

systematic presentations of kabbalistic ideas, such as his Pardes

Rimmonim, a multi-volume commentary on the Torah entitled Or Yakar, and

many other books. He also attracted as his students a number of

individuals who would go on to have a tremendous impact on the spread of

Kabbalistic ideas to the broader Jewish public, including Abraham

ha-Levi Berukhim, Abraham Galante, Smauel Gallico, Mordechai Dato,

Eliezer Asikri, and Elijah de Vidas.

Isaac Luria

Though he spent only a few years in the city of Safed before his

death at a young age in 1572, Isaac Luria had an enormous impact on the

community of Safed kabbalists that permanently transformed the history

of Jewish mysticism. Luria studied briefly with Cordevero when he

arrived in Safed in 1570, but after the latter’s death about six months

later, Luria quickly became the preeminent kabbalist of the community.

Luria’s meteoric rise was not by virtue of his impressive literary

production, since Luria seems to have written little if anything on

Kabbalah at that time. Rather, the force of his impact on the kabbalists

of Safed was through his charismatic personality and the depth and

creativity of his ideas, which he taught orally. Not long after Luria’s

death, hundreds of stories of his spiritual powers, his ability to

perform magical wonders, to determine the origin of a person’s soul or

“soul root,” to read a persons fate by the lines on their forehead and

other such miraculous tales began to circulate, testifying to the kind

of impression Luria made on the imagination of the community. Despite

the fact that Luria wrote very little, his teachings were quickly spread

to the broader Jewish community through the writings of his disciples

who studied with him during the time he was in Safed. Luria’s students,

especially Hayim Vital, went on to write voluminous compositions based

on their master’s teachings. These writings quickly spread Lurianic

Kabbalah throughout the Jewish communities of North Africa and Europe.

Luria’s kabbalistic teachings were often presented as interpretations

of the Zohar, though his symbolism of the ten sefirot becomes

significantly more complex with multiple levels and permutations. Luria

expanded upon a number of important elements already present in one form

or another in Zoharic Kabbalah, such as the coming of the Messiah, the

process of creation through tzimtzum or divine self-contraction,

shevirat ha-kelim or the “shattering of the vessels” that took place at

certain stage in the process of creation, the tikkun or restoration of

divine light or “sparks” through Jewish actions and religious practice,

and kavvanah or mystical intention necessary for the proper practice of

mitzvoth and prayer. Like the Zohar itself, Luria’s Kabbalah contains

bold and complex imagery regarding the inner dynamics of the divine

realm of the sefirot, and the potential for Jewish actions to rectify –

or destroy – the order of the universe in its relation to God.

Shabbtai Zvi

By the middle of the 17th century, Kabbalah, especially in the form

spread the disciples of Isaac Luria, was widely disseminated throughout

the Jewish world. The strong messianic inclination of Lurianic thinking,

coupled with a number of traumatic political events – most notably the

Chmielnicki massacres of 1648, which destroyed hundreds of Jewish

communities throughout eastern Europe and killed many thousands –

contributed to the vast popularity of the messianic movement that

developed around the charismatic figure Shabbetai Zevi. Born in Ismir to

a wealthy merchant family in 1626, Zevi distinguished himself early in

life as a gifted student. He was also an avid kabbalist known for his

bold tendency to pronounce the divine name, the Tetragrammaton, aloud.

He also, according to the historical accounts, seems to have been

afflicted with severe manic depression, and during his manic phases he

would engage in bizarre deliberate violations of the commandments,

including in one instance, marrying himself to a Torah scroll. In the

spring of 1665 Shabbetai Zevi arrived in Gaza, where he met Nathan of

Gaza, a charismatic kabbalist and renowned healer of the soul. Both

quickly became convinced that Zevi was the messiah, and soon won over

many of the local rabbis in Palestine and Jerusalem. Letter and writings

by Nathan of Gaza, Abraham Miguel Cardozo, and other quickly began to

circulate, in which they employed kabbalistic symbolism to argue that

the Messiah had arrived in the person of Shabbetai Zevi. As the news

spread to the Jewish communities of Europe traumatized by disaster and

primed for messianic redemption in the form of a grand kabbalistic

tiqqun, the Sabbatian movement gained many adherents, including a number

of highly respected rabbis. In the summer of 1666 Zevi was brought

before the Turkish Sultan. The historical accounts of what exactly

happened in that meeting are unclear, but the result is certain-

Shabbtai Zevi converted to Islam. This devastating disappointment

brought the movement to a catastrophic end, with most of Zevi’s

followers abandoning the hopes they had placed in him. For some,

however, the conversion of their Messiah was regarded as a profound

kabbalistic mystery that simply needed time to unfold. The followers of

Shabbtai Zevi who continued to believe in his messianic identity

generally held their belief in secret, and are referred to as crypto

Sabbatians. This group developed a complex system of kabbalistic

explanation of the life and actions of Shabbetai Zevi. Adherents to the

Sabbatian doctrine persisted for several generations, and some exist

until today in small numbers. Another small group of Jews at the time of

Zevi’s conversion converted to Islam themselves, creating a secret sect

known as the Donmeh, who outwardly practiced Islam, but secretly

preserved a form of Sabbatian kabbalah.

18th Century Kabbalah and The Rise of Hasidism

After the Sabbatian debacle in the late 17th century, kabbalists

became more conservative in the way they discussed and wrote about their

mystical ideas, in particular with regard to messianic speculation.

Most focused their attention on reconciling the details of Lurianic

Kabbalah with the Zohar, and the interpretation of works by earlier

authorities. 18th century kabbalistic circles in Ashkenazi lands

included Bezalel b. Solomon of Slutsk, Berachiah Berakh Spira, Hayyim b.

Menahem Zanzer (d. 1783), and Moses b. Hillel Ostrer (from Ostrog; d.

1785). In Lithuania, Elijah ben Solomon Zalman of Vilna, also known as

the Vilna Gaon, was a towering rabbinic authority and Kabbalist. In the

Sephardic Jewish communities, Hayyim ha-Kohen of Aleppo and Elijah

ha-Kohen ha-Itamari of Smyrna and many others were active kabbalists who

wrote extensively. Kabbalah played an important role in the religious

life of Jewish communities in Yemen and Kurdistan through the works of

such figures as Shalom b. Joseph Shabasi and Joseph Zalah.

An intriguing school of kabbalists developed in Jerusalem in the mid

18th century at the Beit El yeshiva under the leadership of the Yemenite

kabbalist Shalom Mizrahi Sharabi, who focused on Lurianic Kabbalah,

with a particular emphasis on contemplative prayer. Members of the Bei

El yeshiva, which continued to be active for two hundred years until it

was destroyed by an earthquake in 1927, dedicated themselves to rigorous

regimens of prayer and study. Sharabi and his school came to be

recognized as the main authorities of Kabbalah for Jews living in the

Muslim world, and Sharabi himself acquired a reputation as a kabbalist

almost on a par with Isaac Luria. Some of the most important kabbalists

from the Beit El yeshiva include Abraham Azulai of Marrakesh (d. 1741),

Abraham Tobiana of Algiers (d. 1793), Shalom Buzaglo of Marrakesh (d.

1780), Joseph Sadboon of Tunis (18th century), Jacob Abi-Hasira (d.

1880); Sasson b. Mordecai Shandookh (1747–1830) Joseph Hayyim b. Elijah

(d. 1909).

Israel Baal Shem Tov and the Rise of Hasidism

In the middle of the 18th century a new social phenomenon in the

Jewish world began to take root in Poland-Lithuania, centered around the

kabbalistic traditions and teaching of Israel b. Eliezer Ba’al Shem

Tov, also know as the Besht. The Hasidic movement, as it came to be

called, emphasized a democratic religious ideal wherein spiritual

achievement is attainable through sincerity, piety and joyful worship.

That is not to say that the movement did not have an intellectual

component was well – thousands of Hasidic books and treatises were

composed in the first few generations of the movement, most of which are

infused with kabbalistic motifs and images. As the Hasidic movement

gained wide popularity in eastern Europe throughout the 18th and 19th

centuries, many elements of the Kabbalah became widely known to the

general Jewish public, and Hasidic masters would often incorporate

kabbalistic symbols into their sermons and teachings for their

communities.

Starting in Podolye, the Besht became famous as a magical healer and

wonder-worker – the name “Baal Shem Tov” means “Master of the Good Name”

and related to the kabbalistic notion of the power of divine names.

Some of his most influential students included Jacob Joseph of

Polonnoye, who wrote Toledot Ya’akov Yosef in1780 which was the first

written articulation of Hasidism, and Dov Baer of Mezhirech, who became

the leader of the second generation of Hasidic Rabbis after the death of

the Besht in 1760. Dov Ber’s followers included some who would go on to

become renowned leaders of Hasidic communities and authors of important

Hasidic works, such as Shneur Zalman of Lyady, Levi Isaac of Berdichev,

Aaron (the Great) of Karlin, and Samuel Shmelke Horowitz. Some Hasidic

Rabbis became the heads of dynasties that grew over time to include

thousands of followers. Some groups still active today, such as Chabad

Lubavitch and Breslov, continue to spread their kabbalistically infused

teachings to broader Jewish audiences.

Kabbalah in the 20th and 21 Centuries

In addition to the many Hasidic Rabbis and desciples of the Beit El

yeshiva who remained active into the 20th century, individuals such as

Yehudah Ashlag and his disciple and brother-in-law Yehudah Zevi

Brandwein continued to develop and spread knowledge about kabbalistic

texts and ideas. Ashlag, who was born in Warsaw but moved to Jerusalem

in 1920, composed many important texts and commentaries on the works of

earlier kabbalists, including the famous Ma’alot ha-Sullam (1945–60)

commentary and translation of the Zohar in 22 volumes, completed by his

brother-in-law after his death. Brandwein also wrote commentaries on the

works of Moses Cordevero and Isaac Luria, as well as a complete library

of Lurianic Kabbalah in 14 volumes. Abraham Isaac Kook, the founding

thinker of religious Zionism, was also and avid kabbalists who sought to

apply his mystical teaching in social and political action.

In the late 1960’s Philip Berg, born Shraga Feivel Gruberger in

Brooklyn, New York, traveled to Jerusalem where he studied with Yehudah

Zevi Brandwein. Berg began to open institutes for the study and teaching

of Kabbalah, first in Tel Aviv, followed by many more branches

throughout the United States and Europe. The branches of Berg’s

institute came to be known as The Kabbalah Center, with its main

headquarters in Los Angeles, where a number of American celebrities,

most notably Madonna, have become associated with the movement. Bergs’

main goal in developing The Kabbalah Center is to spread kabbalistic

ideas in ways that are comprehensible and practical in everyone’s daily

life. Critics of The Kabbalah Center have argued that Berg’s movement is

nothing more than a cynical ploy to profit financially by selling a

form of New Age spirituality under the guise of genuine historical

Kabbalah to an unsuspecting public. Sales in books, classes, online

tutorials, “Kabbalah water,” and red string bracelets bring are a

multi-million dollar money maker for The Kabbalah Center. Today the

center is co-directed by Berg’s sons, Yehudah and Michael Berg.